Missing Teeth? Find Your Smile Again.

How a 19th Century Battlefield Solved the Problem of Bad Dentures

Language :

Topics:

The Chilling Smile: How a Battlefield's Secret Revolutionized Dentures

Welcome to the "Bagong Ngiti" Blog – Where we explore the incredible history and future of your smile.

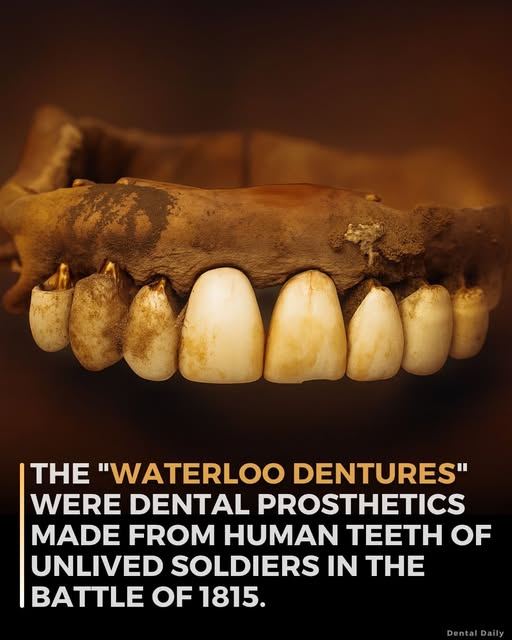

We often think of modern dentistry as a realm of 3D printers, digital implants, and biocompatible materials. But the quest for a perfect, durable smile has a much darker and more fascinating history. Long before the era of acrylic and porcelain, the most sought-after dentures in the world had a grim origin story—they were built with teeth harvested from the dead of the battlefield.

This is the story of the "Waterloo Denture," a prosthesis that could last for decades, born from the aftermath of one of history's most famous conflicts.

The Battlefield Harvest: An Unlikely Dental Supply

In the summer of 1815, the Battle of Waterloo left tens of thousands of soldiers dead on the fields of Belgium. Amid the tragedy, a macabre trade emerged. "Tooth traders" scoured the battlefield, not for valuables, but for something surprisingly specific: the intact, healthy teeth of young adult men.

These teeth, prized for their strength and appearance, were collected by the barrel-load. They were cleaned, sorted, and shipped to dental workshops across Europe, primarily in Britain. For the denturists of the early 19th century, this was a gold rush. Here was a supply of pristine, real human enamel that was far superior to anything else available.

Why "Waterloo Teeth" Were the Gold Standard

Before this grisly discovery, denture options were bleak for those who could afford them.

-

Ivory Dentures: Carved from elephant or hippopotamus tusks, they were expensive, bulky, and wore down quickly, leading to a constantly changing bite and unpleasant taste.

-

Poorer Alternatives: The less affluent might use teeth from animals or even other humans, but rarely in such quantity or quality.

The "Waterloo teeth" changed everything. Real human enamel is incredibly hard-wearing. Unlike ivory, it didn't rapidly deteriorate with chewing. This meant that a set of dentures crafted from these harvested teeth could last for 20, 30, or even more years—a lifetime for many wearers. They looked more natural and functioned better than any prosthetic that had come before.

The Art of the Gruesome: Crafting a Waterloo Denture

These dentures were not primitive. They were masterpieces of early 19th-century craftsmanship, built for the wealthy elite.

-

The Base: A denturist would carve a baseplate from ivory, shaped to fit the patient's palate.

-

The Set-Up: The harvested human teeth were carefully selected for size and color, then arranged in a lifelike arch.

-

The Mounting: The teeth were secured to the ivory base with tiny gold pins or brass wires. Gold springs were sometimes used to help the upper and lower plates separate naturally.

For a patient, it was the closest thing to having their own smile restored. They were unaware, or perhaps willfully ignorant, of the true cost of their new teeth.

The End of an Era

The reign of the "Waterloo denture" lasted for decades, but it couldn't last forever. The supply of battlefield teeth eventually dwindled. More importantly, the 1840s brought two key innovations:

-

Vulcanized Rubber: This provided a cheap, comfortable, and easily molded base material, replacing the bulky and expensive ivory.

-

Mineral Porcelain Teeth: The development of durable, lifelike porcelain teeth finally offered a consistent and ethical alternative to harvested human teeth.

The market for "Waterloo teeth" vanished almost overnight.

A Sobering Legacy

The story of Waterloo dentures is a strange and sobering chapter in dental history. It highlights a time when the line between life and death, dignity and commerce, was starkly blurred in the pursuit of health and beauty. It was a solution born from tragedy, a stark reminder of how far dentistry has come—not just in its technology, but in its ethics and humanity.

Today, we restore smiles with space-age polymers, titanium implants, and digital scans. But the driving desire behind it—the wish to chew, to smile, to live without shame—is a human constant, connecting us directly to those who, two centuries ago, wore a smile built on a battlefield.